The Gender of Madness

Literature romanticises male madness as the “mad genius,” the “wild man,” the “rebel.” These terms carry a strange dignity as men are celebrated madmen. By contrast, women are more often cast in the language of pathology: “hysterical,” “emotional,” “untamed.” One is transcendent; the other, unstable.

But who gets to be wild? Who gets forgiven for chaos? What are the conditions under which someone is permitted to be ‘mad’ and still celebrated?

Socially, a man dancing wildly is “letting loose”, a woman doing the same is characterised as desperate, vulgar or irresponsible. The gaze does not shift; its judgment does.

I am very big on letting loose. I dance like I literally know nobody is watching. But, imagine a man spinning on the dancefloor (arms flinging around, presumably hitting a few people), drunk. Onlookers would say, “he’s mad”, but not as a judgment. It’s admiration. “Mad”, a social crown. A simple man, unbound from self-consciousness….When men unravel, we celebrate their passion. Their chaos is read as authenticity. Their disarray becomes a kind of genius.

But again, who gets to be wild? Who is permitted to lose control and still be whole? Still be desirable? Still be safe?

We don’t just witness this on dance floors. We see it in cinema, in politics, in homes. The male artist who isolates himself and screams at assistants is labelled a tortured visionary. The woman who cries in a boardroom is seen as unprofessional, unfit. Even when the end results are equally brilliant (or equally messy) chaos in a man’s hands is viewed as the price of greatness. In a woman’s hands, it becomes evidence of incapacity.

Across industries and cultures, we have learned to read masculine breakdowns as moments of breakthrough. Female ones? As breakdowns, full stop.

Think of the literary canon. Hamlet’s madness is philosophical, layered, profound. Ophelia’s is ornamental, pretty and tragic, a consequence of love. In The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath captures this double bind precisely. Her protagonist descends into depression, and it consumes her. Meanwhile, her male counterparts, Hemingway, Bukowski, Kerouac, are allowed to drink, rage, wander, and still be canonised. Their chaos is part of their legend.

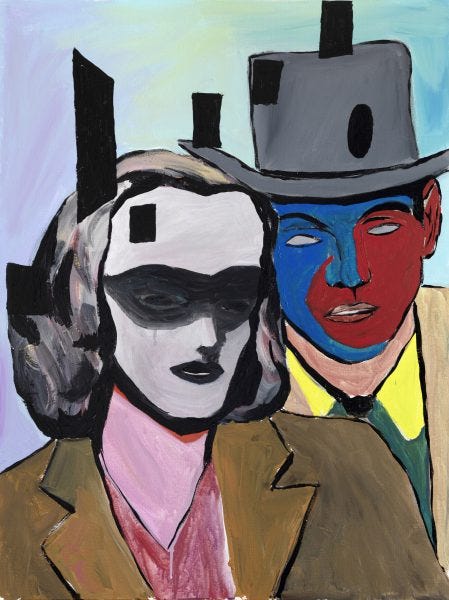

Cinema follows suit. In Joker, Arthur Fleck’s violent spiral is humanised, aestheticised. He dances on stairs, smears blood like face paint, and the camera lingers lovingly. Contrast this with Black Swan, where Nina’s descent is grotesque and horrific. Her madness destroys her. His makes him unforgettable.

Even in politics, the wild man is often granted space to exist. Consider Boris Johnson’s calculated disorder, the rumpled hair, the stammering buffoonery, the gaffes. They became his brand, not his disqualification. Meanwhile, women in public office are punished for the smallest signs of emotional flux. Hillary Clinton’s voice cracking made headlines. Jacinda Ardern’s resignation, framed around burnout and motherhood, became proof (to some) of women’s unfitness for power, rather than a gesture of honesty.

Pop culture feeds the same narrative. Kanye West’s public meltdowns are dissected for signs of genius. Britney Spears’ breakdown became a meme, a punchline, and a legal cage. The permission to unravel is deeply gendered. Men get to be wild and remain whole, sometimes even more powerful in their ruin. For others, madness is the end of the road.

Still, I choose to unravel, consciously, deliberately, even as I navigate the line between freedom and safety. I carry the gaze alongside my joy. I know what it means to be read as inauthentic, arrogant, unfit to lead a team, have a voice or hold space. But who is to stop me? I don’t surrender, I move past.

But I am also writing to acknowledge that this isn’t defiance without awareness. Women gaze back. We know what the room sees. We know what our laughter, our tears, our volume might cost us in settings where men are celebrated for the same.

It is time to rethink what we associate with genius, with power, with freedom. Madness, in its true form, is neither myth nor menace. It is not a costume for men or a punishment for women. It is part of the human condition, and it belongs to all of us.